The Illinois Appellate Court recently issued a decision in a case involving a slip and fall in snow, but the interesting part about the case is that it does not involve the natural accumulation doctrine. Instead, the defendants argued the snow pile was open and obvious to obtain summary judgment, which is quite unique.

The Illinois Appellate Court recently issued a decision in a case involving a slip and fall in snow, but the interesting part about the case is that it does not involve the natural accumulation doctrine. Instead, the defendants argued the snow pile was open and obvious to obtain summary judgment, which is quite unique.

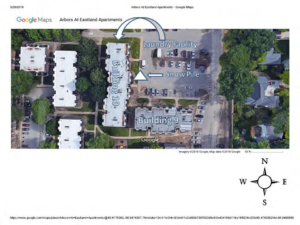

In Winters v. MIMG LII Arbors At Eastland, LLC, 2018 IL App (4th) 170669, the plaintiff was a tenant in an apartment complex and he filed suit against the owners of the apartment complex and the vendor responsible for snow removal at the property. The plaintiff claimed the snow vendor pushed snow from the parking lot onto the sidewalk, so the snow was completely covering a portion of the sidewalk. The plaintiff was walking from his apartment to the on-site laundry when he encountered the snow pile on the sidewalk and was forced to navigate around it, but slipped and fell in the process.

Relevant Facts:

- Plaintiff saw the pile of snow before he encountered it and his visibility was not blocked.

- There was a cut-out through the snow pile where others had walked through it.

- He was able to see where he was walking as he walked and he knew he was walking on snow and ice.

- Plaintiff admitted there were at least two alternative paths he could have taken to get to the laundry at that time.

- A vendor employee testified he believed he was authorized to pile snow on the sidewalk but the sidewalk was not his responsibility to clear so it would be up to a property maintenance employee to then clear the sidewalk of that snow.

- The property maintenance employee testified there was so much snow on the sidewalk and it was so hard that he could not remove it with a snow blower.

The defendant snow vendor filed a motion for summary judgment arguing it owed no duty because the snow pile was an open and obvious condition and the property owner filed the same motion a few months later. The trial court granted both motions and the plaintiff appealed.

The appellate court first noted that when determining whether a duty exists, courts primarily consider the four traditional duty factors. These four duty factors are: (1) the likelihood of injury, (2) the reasonable foreseeability of injury, (3) the magnitude of the burden of guarding against the injury, and (4) the consequences of placing that burden on the defendant. Simpkins v. CSX Transportation, Inc., 2012 IL 110662, ¶ 18. The appellate court also noted that courts also consider public policy when determining whether a duty exists. Id. ¶ 17. If a duty is found to exist, the general rule is that a defendant owes his or her invitees and licensees a duty of reasonable care under the circumstances. Grant v. South Roxana Dad’s Club, 381 Ill. App. 3d 665, 673, 886 N.E.2d 543, 551 (2008).

The open and obvious doctrine is directed at the first and second duty factors. Bruns v. City of Centralia, 2014 IL 116998, ¶ 19; Wilfong v. L.J. Dodd Construction, 401 Ill. App. 3d 1044, 1056 (2010). A condition is “open and obvious” when a reasonable person in the plaintiff’s position, exercising ordinary perception, intelligence, and judgment, would recognize both the condition and the risk involved. Olson v. Williams All Seasons Co., 2012 IL App (2d) 110818, ¶ 42. Normally, the open and obvious doctrine applies to conditions like fire or bodies of water; however, it can extend to other conditions such as sidewalk defects. Burns v. City of Chicago, 2016 IL App (1st) 151925, ¶ 45.

The two exceptions to the open and obvious doctrine are: (1) the distraction exception; and (2) the deliberate encounter exception. Sollami v. Eaton, 201 Ill. 2d 1, 15 (2002). The distraction exception applies when the landowner has reason to expect the customer may be distracted and will therefore fail to discover or protect against the open and obvious danger. This exception applies only when evidence exists from which the court can infer that the plaintiff was actually distracted. City of Centralia, 2014 IL 116998, ¶ 22.

The deliberate encounter exception applies when the landowner has reason to expect the customer will proceed to encounter the known or obvious danger because a reasonable person in the plaintiff’s position would do so. Sollami, 201 Ill. 2d at 15. The deliberate encounter exception is usually applied in cases involving some kind of economic compulsion but economic compulsion is not a per se requirement of the deliberate encounter exception. Id.

In this case, no one disputed the physical nature of the snow pile. The plaintiff testified his visibility was not obstructed on the day he fell and he was aware of the pile of snow. He also testified that as he was walking on the pile of snow, he knew he was walking on snow and ice. The court determined that based on this testimony, a reasonable person in the plaintiff’s position, exercising ordinary perception, intelligence, and judgment, would have noticed the large pile of snow and realized the risk of walking upon it. Therefore, the appellate court ruled as a matter of law that the snow pile was an open and obvious condition.

The plaintiff argued that even though the snow pile was open and obvious, there was a question of fact as to whether the deliberate encounter exception applied but the court disagreed. The plaintiff admitted there were several other routes he could have taken but he chose to walk through the snow pile. The facts were also not consistent with other cases where the deliberate encounter exception was applied. The plaintiff was not at his place of employment or facing any other type of economic compulsion. The plaintiff was aware of other reasonable alternative routes to the laundry facility, but instead of choosing to take an alternative route, he proceeded upon a path which had a large pile of snow. He then walked over this snow pile and fell. The plaintiff failed to demonstrate that a reasonable person in his position would have found greater utility in choosing to walk over the snow pile instead of using one of the alternative paths. For these reasons, summary judgment was affirmed for both defendants.

This case is a great example of an alternative defense to use when the natural accumulation doctrine is not available.